My research explores Ancient Maya art, archaeology, and hieroglyphic writing, and what it can tell us about the society that created it. This research has focused on two major themes: politics of Maya religious belief and ritual, and the changing Late Classic political economy. My approach is semiotic–viewing ancient people as active creators and manipulators of material and linguistic signs in their creation of political institutions. Methodologically, these projects use three main methodological approaches: the analysis of art, architecture, and material culture from archaeological sites and museum collections; the interpretation of hieroglyphic texts; and the study of archival materials with the help of digital techniques. Below, read more about these themes and approaches, and see the Curriculum Vitae page for publications.

Patrons and Adversaries: Semiotics of Maya Religious Ritual

This Early Classic stela on view at the Princeton University Art Museum describes an offering ritual for local deities.

Art, Archaeology, and Material Culture: as a graduate student on the La Corona Regional Archaeology Project, I explored patron deity and ancestor veneration in a set of small temples. As factions of this ancient community struggled for control and foreign patronage, they used competing religious practices to argue for their own right to rule the community. The participation of community members in veneration practices is revealed by the ceramics left in temples middens and on terraces.

Hieroglyphic texts: across the lowlands, Maya communities venerated their own local deities, who they saw as protectors and patrons. Rulers explicitly linked their political claims to their relationships with these patrons. I argue that the these local cults thwarted the imperial ambitions of the most powerful Classic period kingdoms, and that large-scale unification under the postclassic Mayapan confederacy only became possible when this local deity model was replaced.

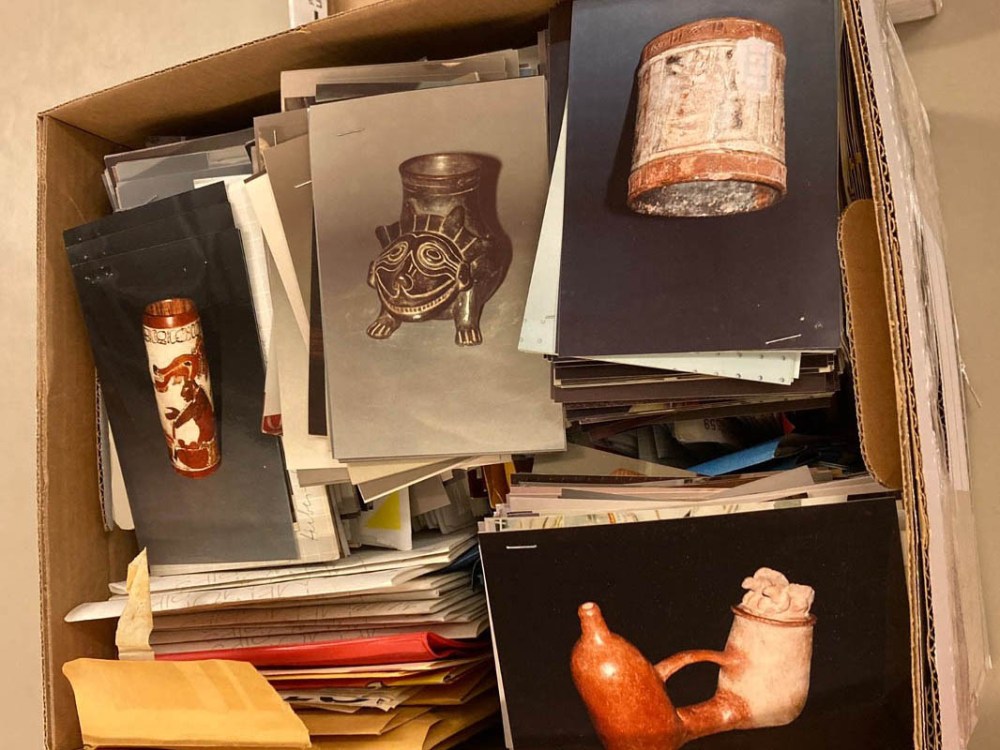

Archives: Maya deities and wahys–sinister supernatural characters representing disease and misfortune–were represented in greater quantity on decorated ceramics than any other medium. The Justin Kerr photographic archive of Maya pottery at Dumbarton Oaks contains hundreds of examples. Digitally cataloging them allowed patterns to emerge: strategic employment and avoidance of wahy motifs by Classic Maya ceramic artists reveals new links between religious narratives Maya geopolitics.

Monetary Registers: the Changing Maya Political Economy

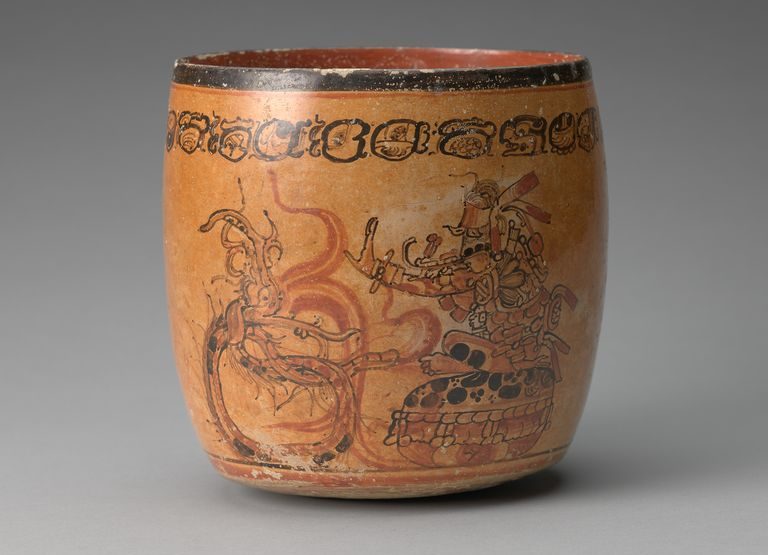

This vase, now on display at the Princeton University Art Museum, was made for a La Florida ruler. Another like it was found at Zaculeu, over 100 miles away.

Art, Archaeology and Material Culture: I directed the La Florida Archaeology Project from 2013 to 2019. The site saw a rapid foundation and settlement in the 7th century, probably due to the growing cacao trade. Its ceramics reveal ties to distant trading partners, and its monuments employ the semiotics of more well-established dynasties. See floridanaranjo.net for more.

Hieroglyphic texts: in the seventh century, Maya scribes and artists began to describe economic relationships in new ways, emphasizing standardization and quantification. Using evidence from over 200 painted ceramic vessels and other textual sources, I argue for the monetization of certain goods during the Late Classic period.

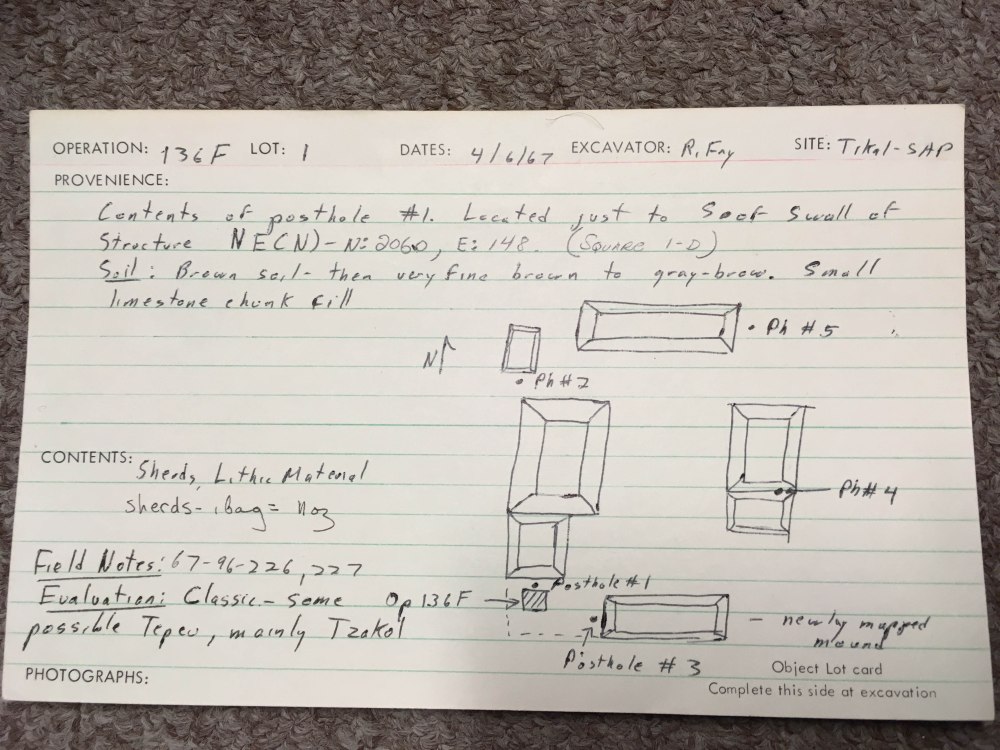

Archives: a re-analysis of textile-production tools excavated across the Maya lowlands, especially from the site of Tikal, reveals that the 7th century Maya began to bifurcate their textile production. While most thread probably continued to be used for the household, some of it was also now produced specifically for the market for for tribute payment.